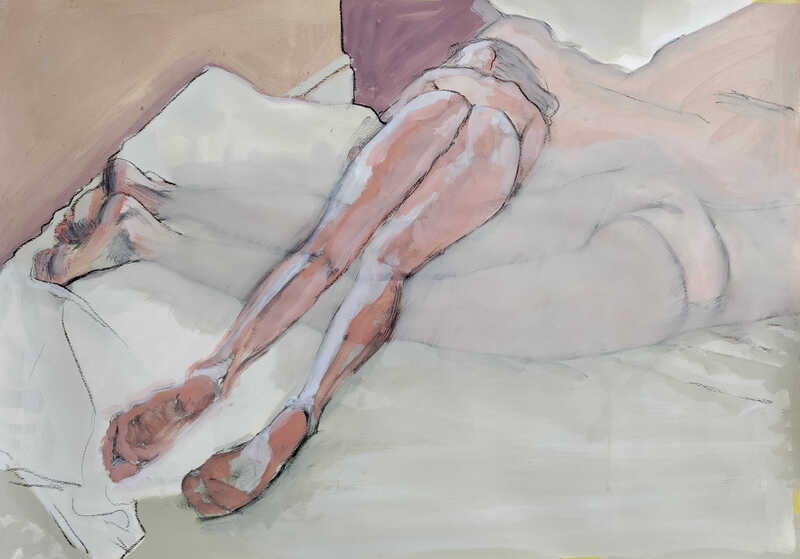

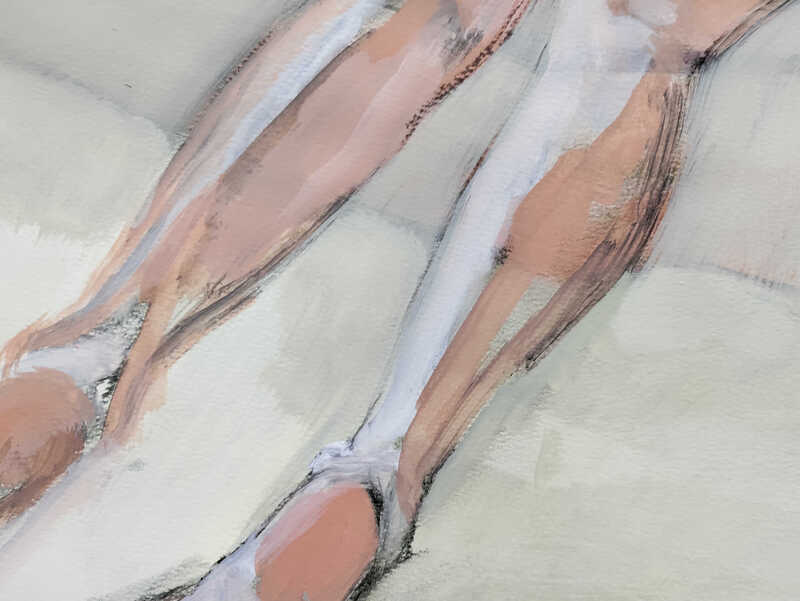

2023/24

DETAILS OF WIP & STUDIES

2022

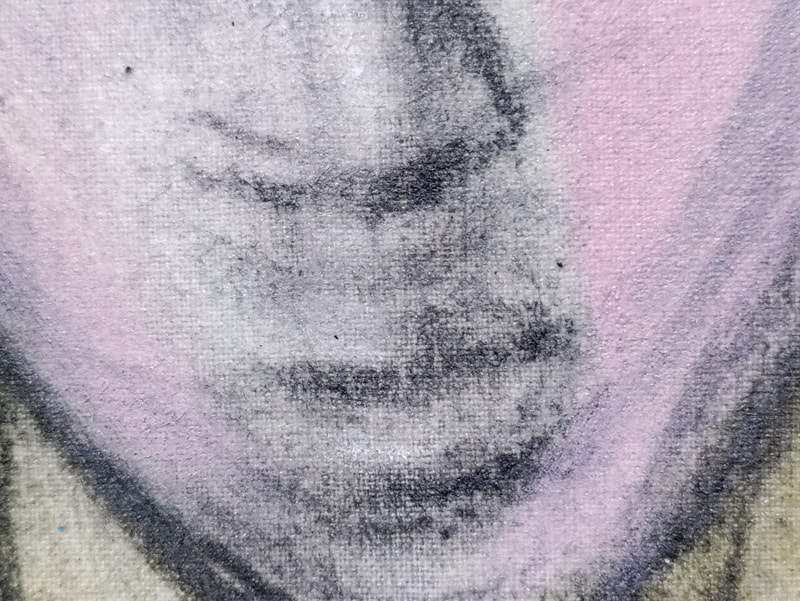

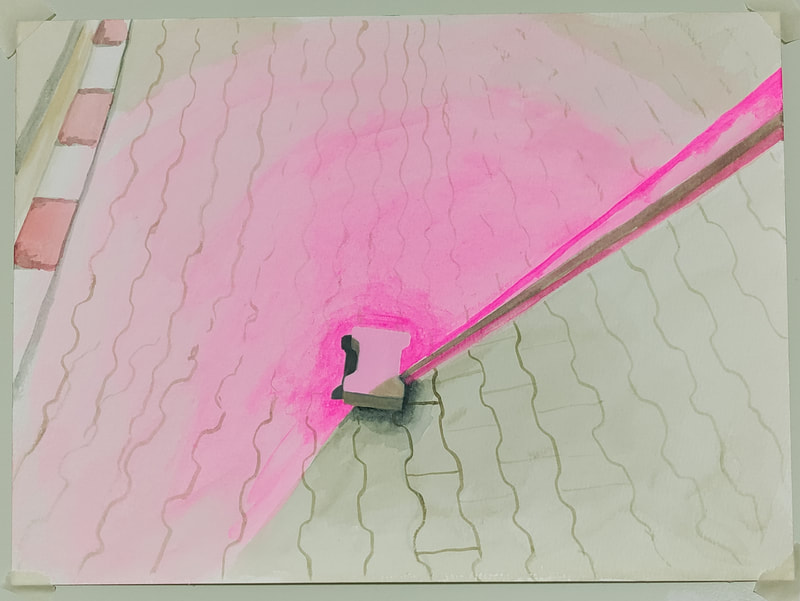

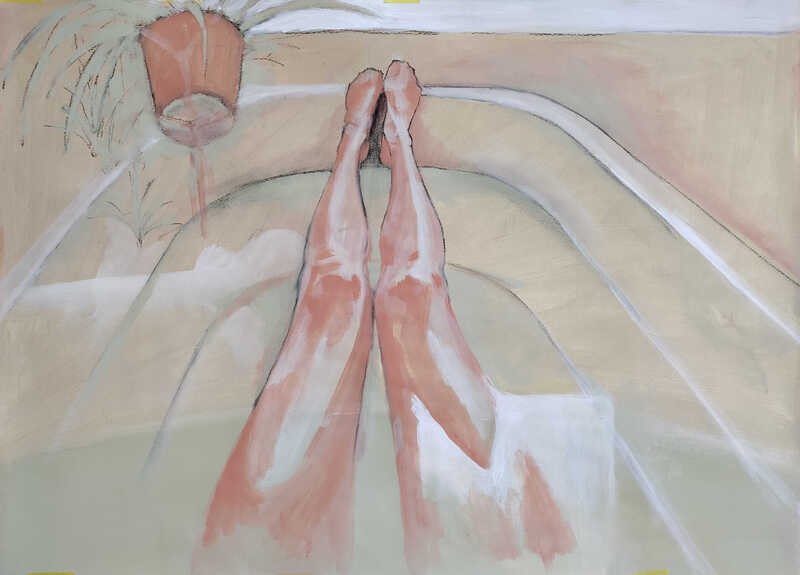

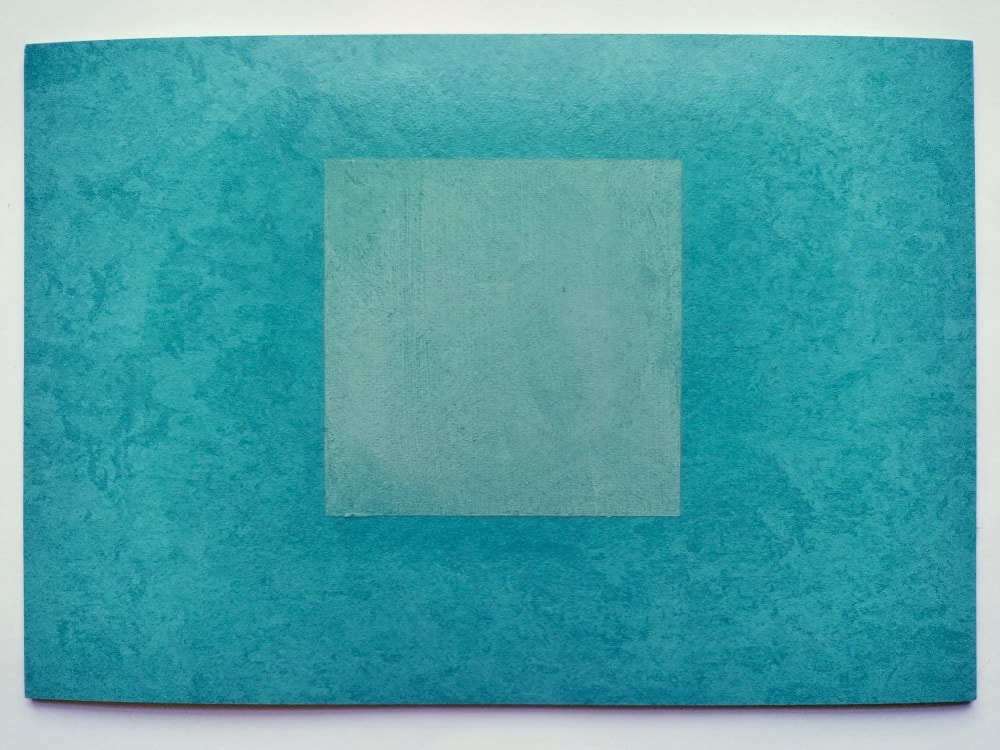

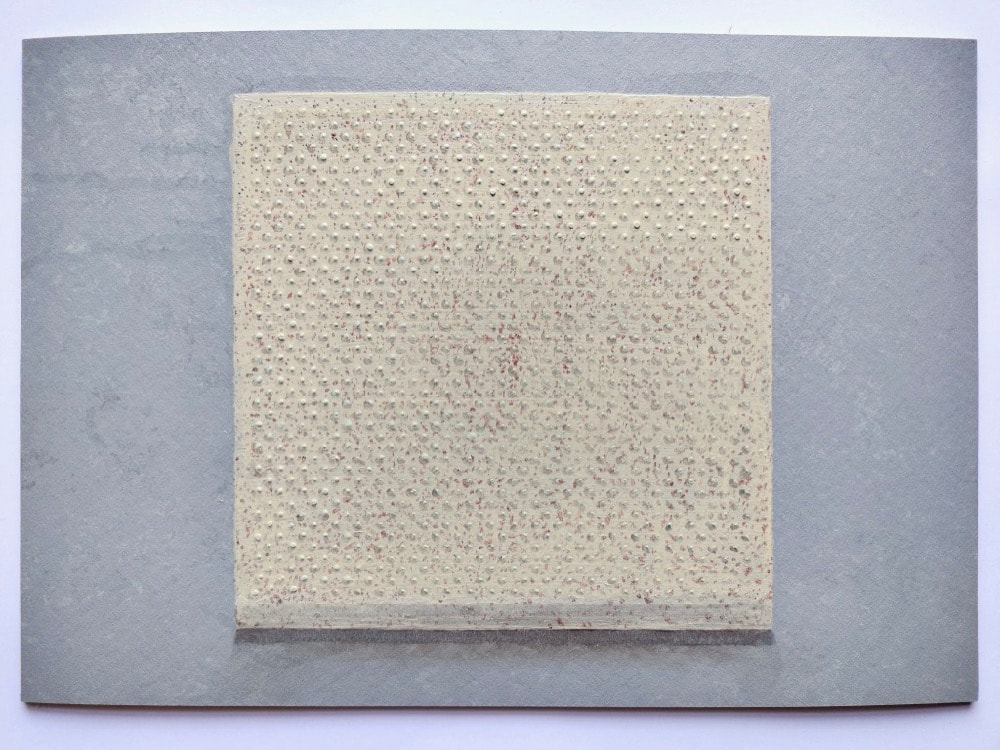

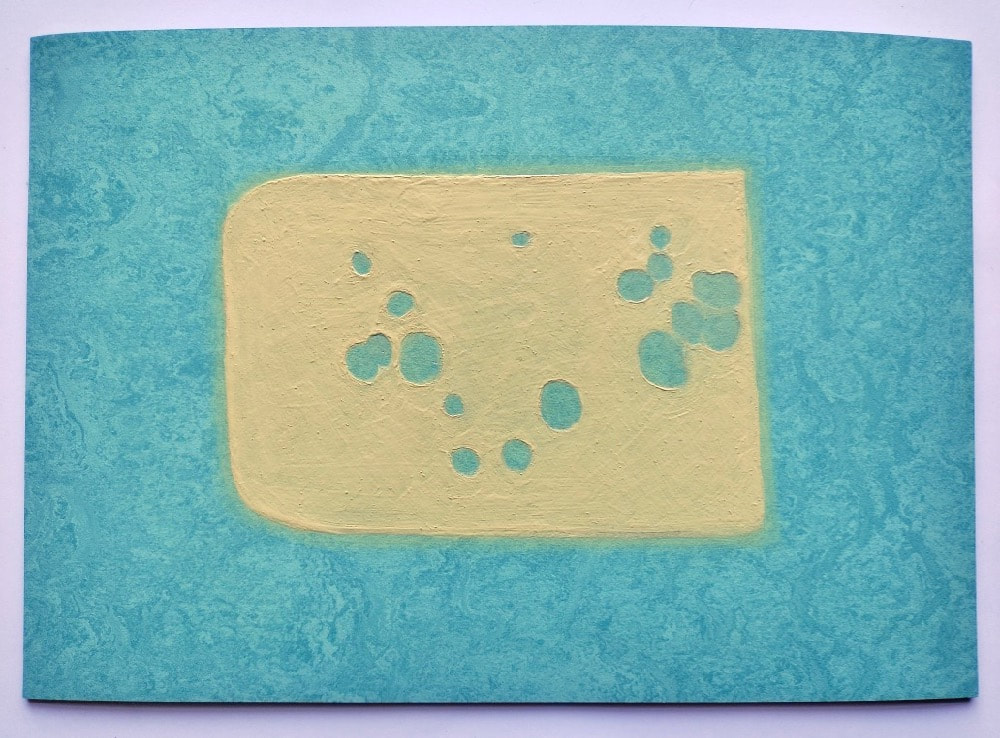

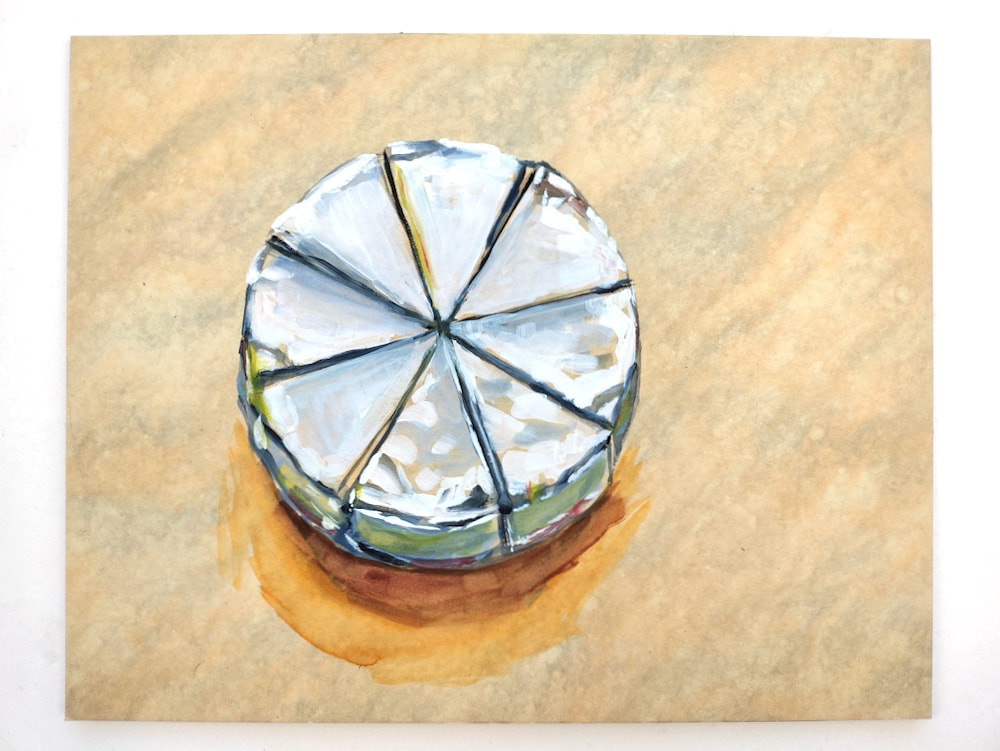

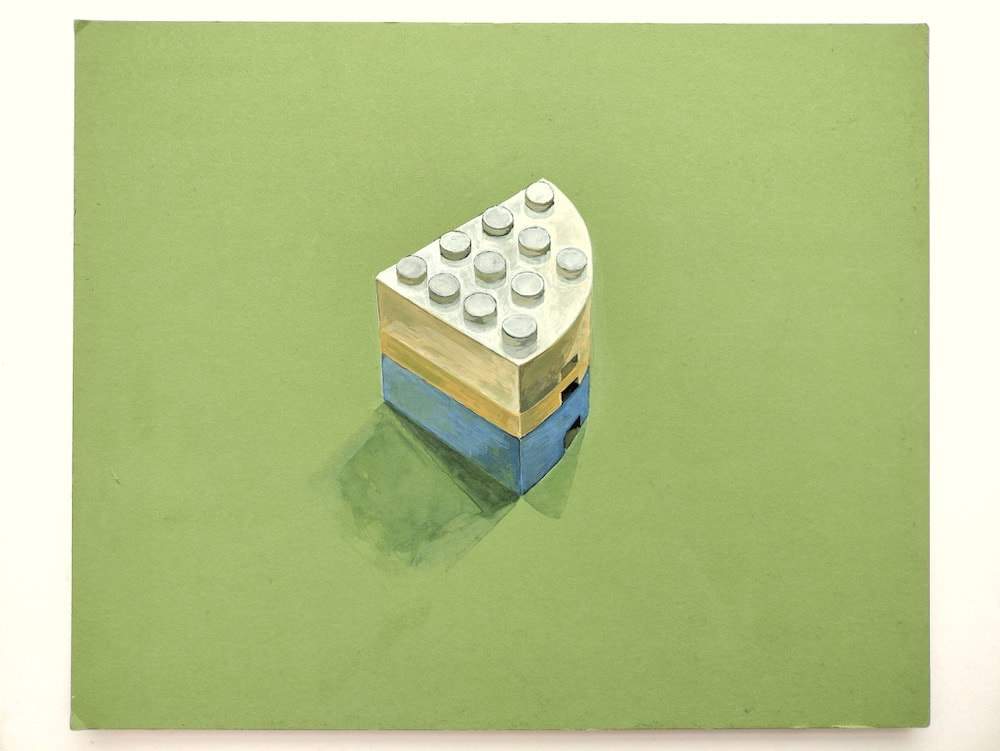

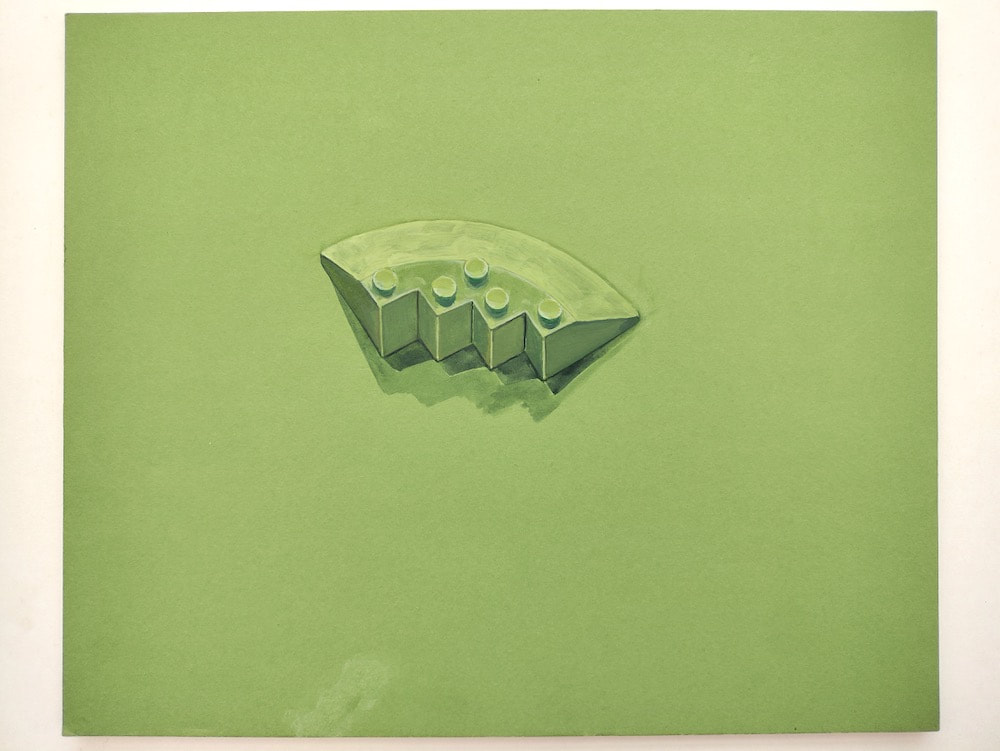

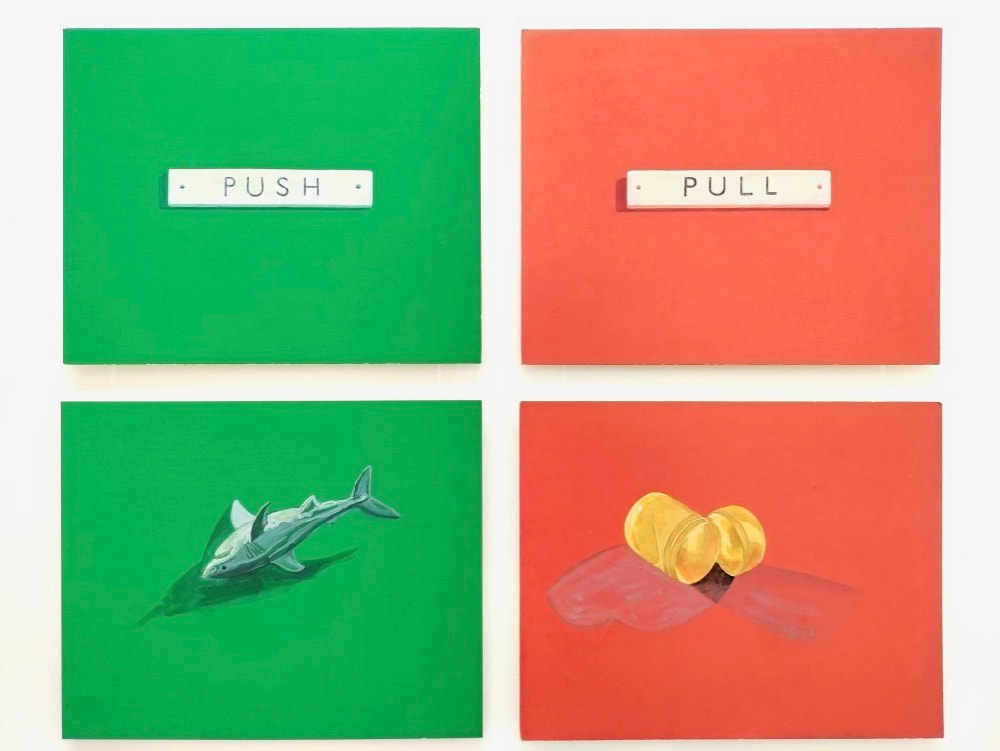

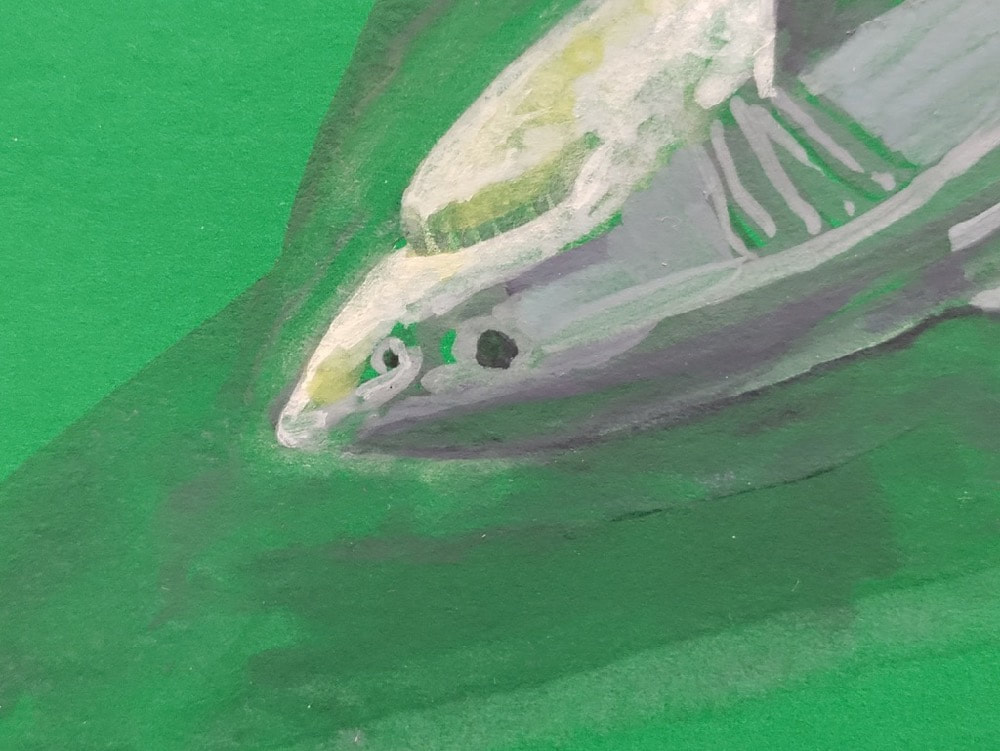

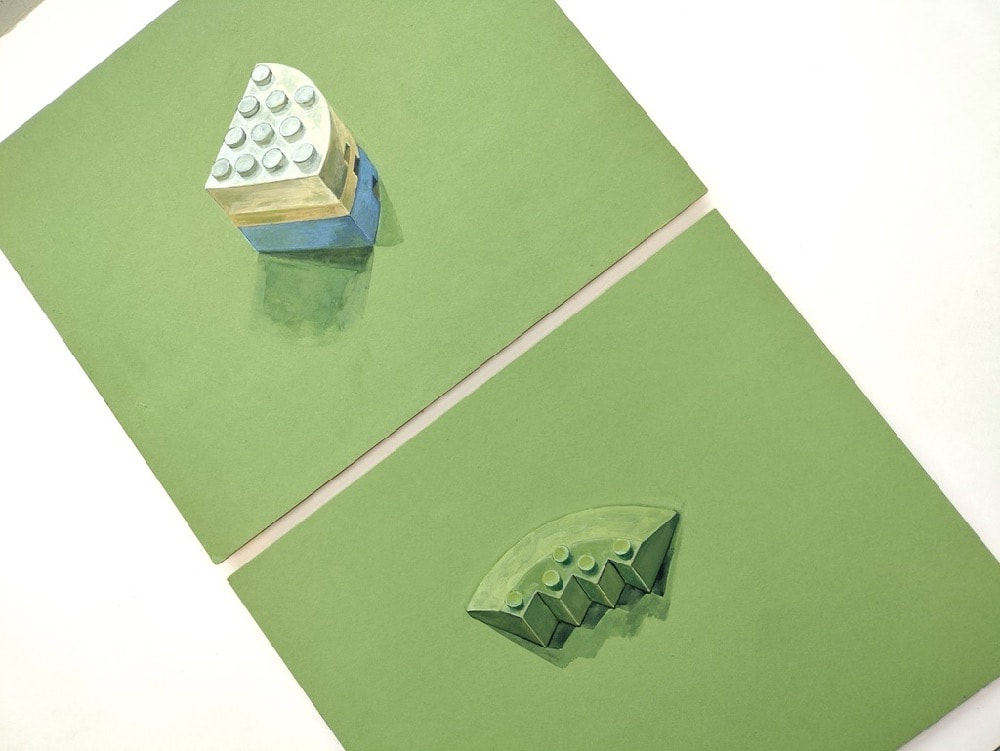

FRESCO CONCRETE PIANO (OIL ON LINOLEUM STUDIES)

FRESCO CONCRETE PIANO

exhibited in The Disoeuvre: Household Mix

20 August – 18 September 2022

Roseville, Ramsgate

Felicity Allen, Denise De Cordova, Moyra Derby, Jane Gifford, Vanessa Jackson, Reem Khatib, Jenny Matthews, Chiara Williams

exhibited in The Disoeuvre: Household Mix

20 August – 18 September 2022

Roseville, Ramsgate

Felicity Allen, Denise De Cordova, Moyra Derby, Jane Gifford, Vanessa Jackson, Reem Khatib, Jenny Matthews, Chiara Williams

The second of an intermittent series of Household exhibitions developed to explore the concept of the Disoeuvre, The Disoeuvre: Household Mix, with artists Felicity Allen, Denise De Cordova, Moyra Derby, Jane Gifford, Vanessa Jackson, Reem Khatib, Jenny Matthews, Chiara Williams opens at Roseville, Ramsgate on 20 August 2022.

The concept of the Disoeuvre has been named and developed by Felicity Allen over the last decade through research and in dialogue with others - see www.felicityallen.co.uk/the-disoeuvre for more info. Recognising the often intermittent nature of an art practice for many women and those who are positioned as marginal to art’s production, the Disoeuvre acknowledges that we have had to work socially and institutionally, as well as in the studio, not only to make work, but to change existing structures so that our work can be recognised and critically received as art. Rather than failure to achieve consistency through an interrupted oeuvre, we can find originality and consistency by tracking work undertaken not only in the studio but, for instance, at home or in paid employment during a career’s apparent interruptions.

Each Disoeuvre Household exhibition manifests an aspect of the Disoeuvre. Household Mix poses four pairs of artists in dialogue with one another, recording conversations, with an underlying question around the use of proxy as a feminist strategy. The pairs are Moyra Derby with Vanessa Jackson, Denise de Cordova with Jane Gifford, Reem Khatib with Jenny Matthews, Felicity Allen with Chiara Williams

More information: https://felicityallen.co.uk/the-disoeuvre

The concept of the Disoeuvre has been named and developed by Felicity Allen over the last decade through research and in dialogue with others - see www.felicityallen.co.uk/the-disoeuvre for more info. Recognising the often intermittent nature of an art practice for many women and those who are positioned as marginal to art’s production, the Disoeuvre acknowledges that we have had to work socially and institutionally, as well as in the studio, not only to make work, but to change existing structures so that our work can be recognised and critically received as art. Rather than failure to achieve consistency through an interrupted oeuvre, we can find originality and consistency by tracking work undertaken not only in the studio but, for instance, at home or in paid employment during a career’s apparent interruptions.

Each Disoeuvre Household exhibition manifests an aspect of the Disoeuvre. Household Mix poses four pairs of artists in dialogue with one another, recording conversations, with an underlying question around the use of proxy as a feminist strategy. The pairs are Moyra Derby with Vanessa Jackson, Denise de Cordova with Jane Gifford, Reem Khatib with Jenny Matthews, Felicity Allen with Chiara Williams

More information: https://felicityallen.co.uk/the-disoeuvre

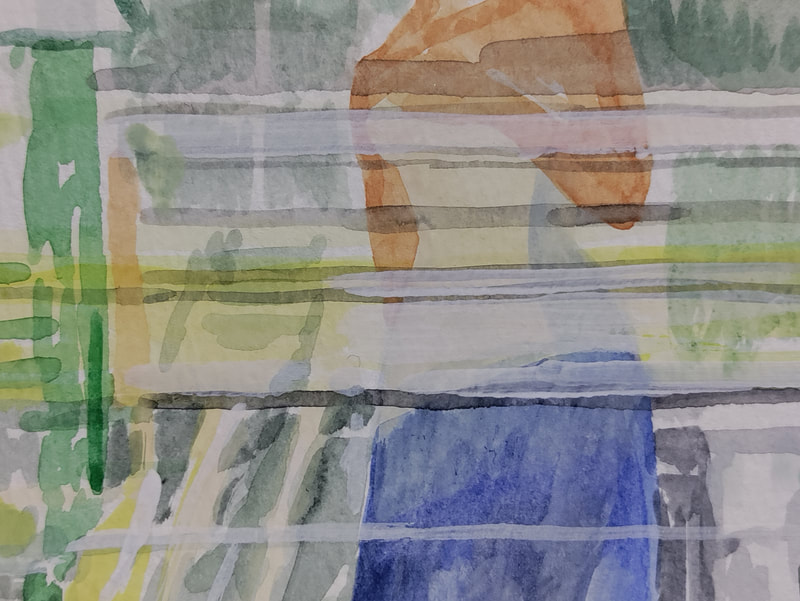

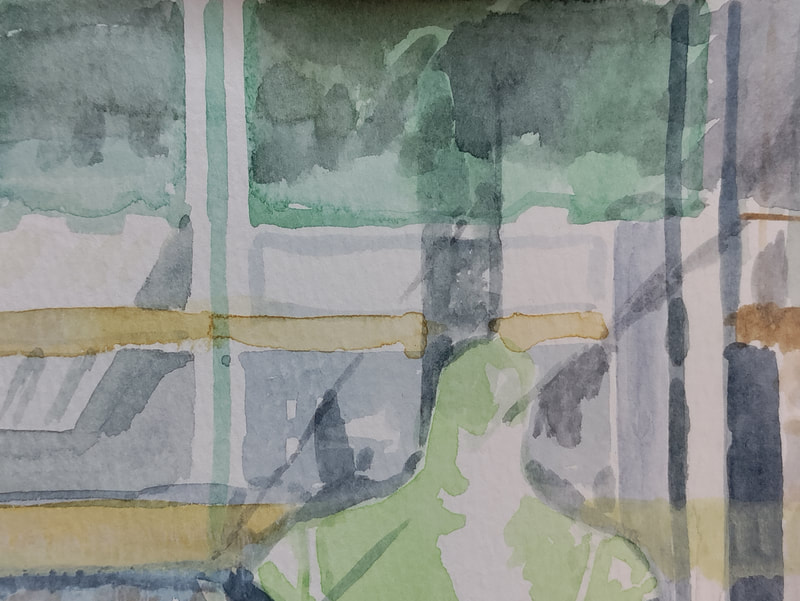

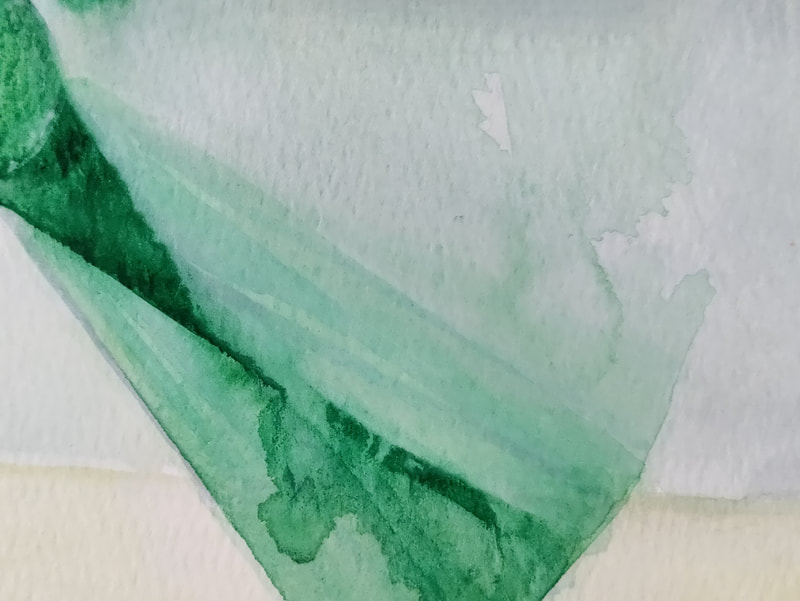

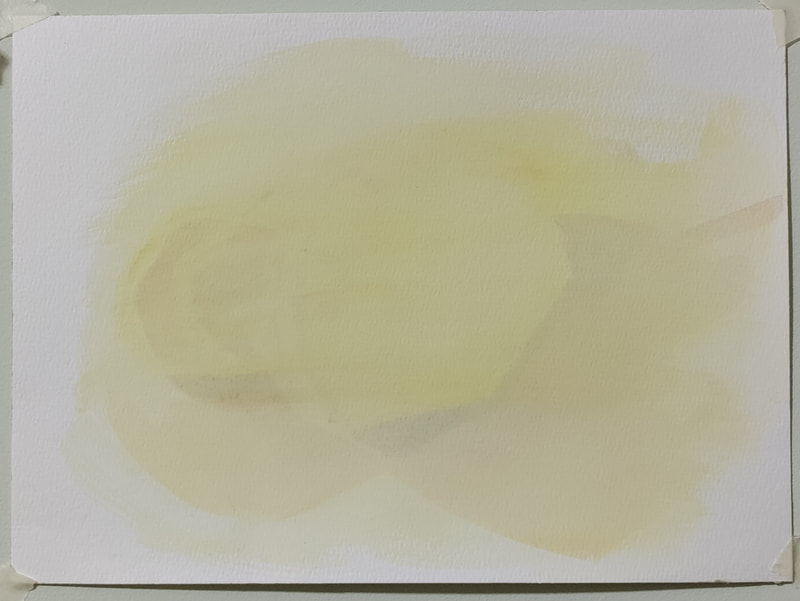

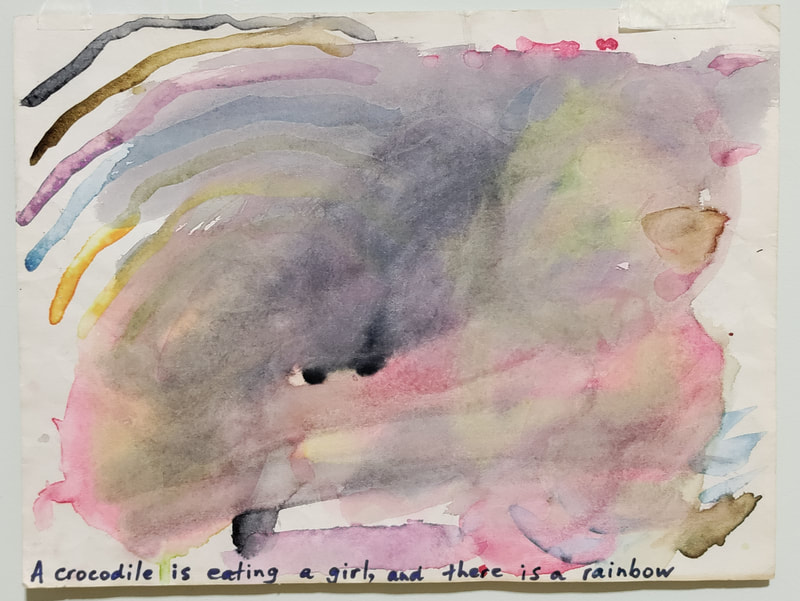

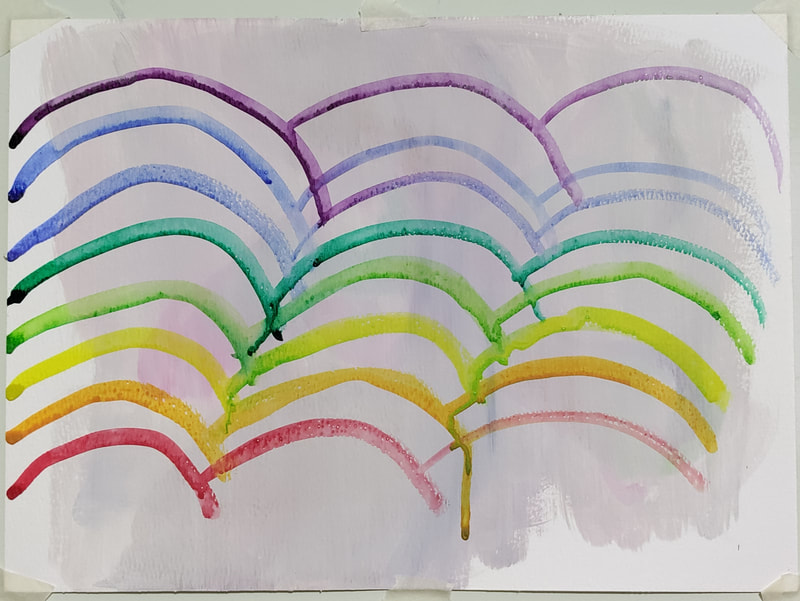

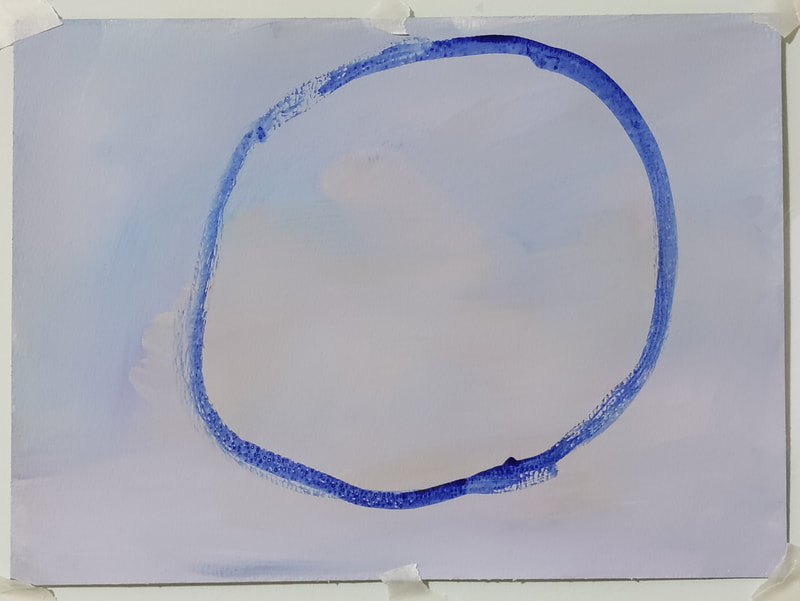

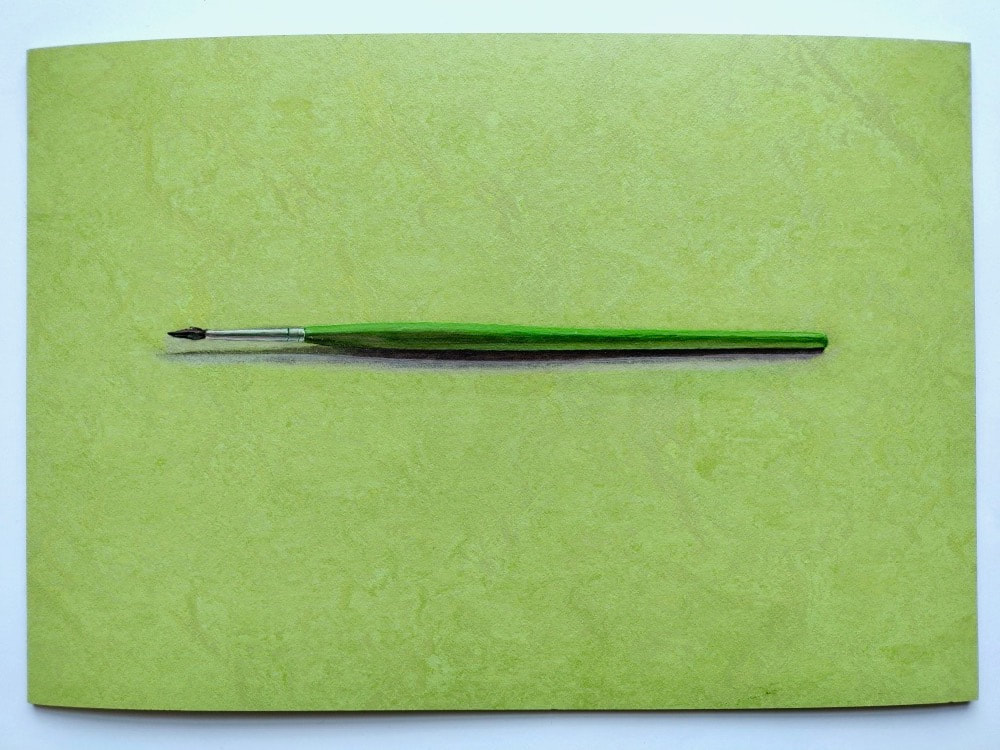

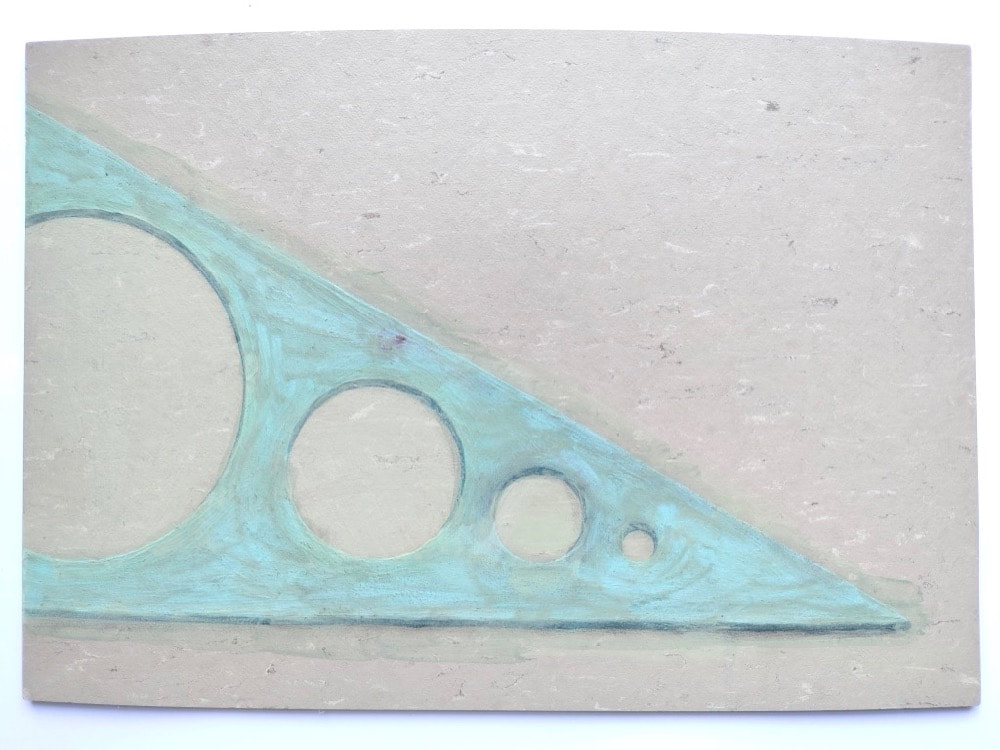

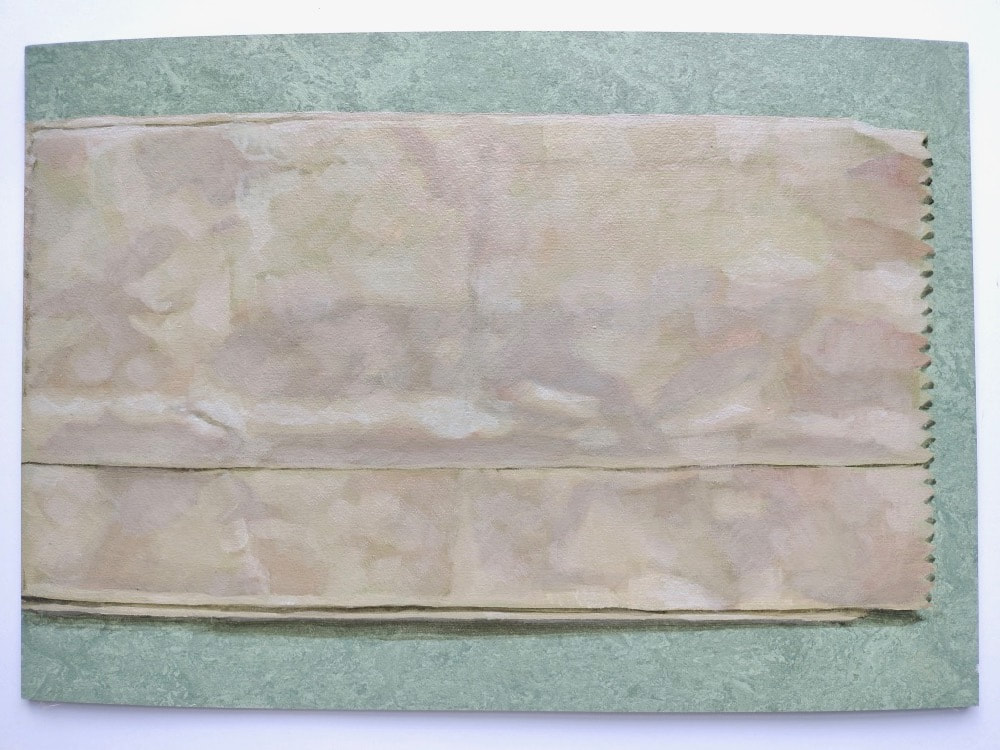

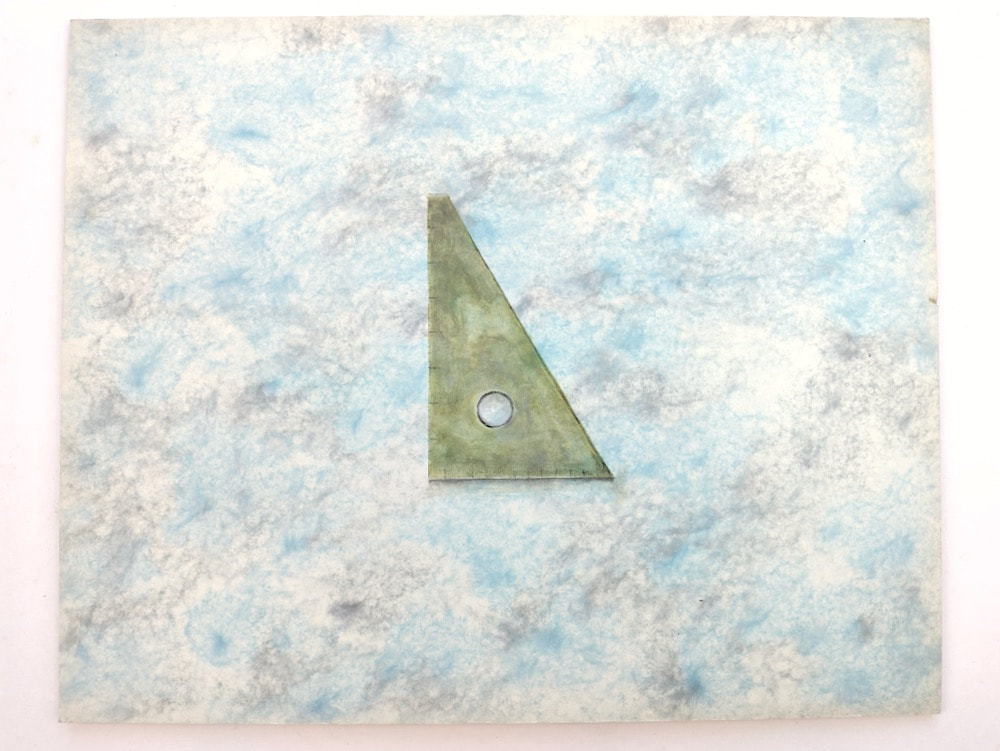

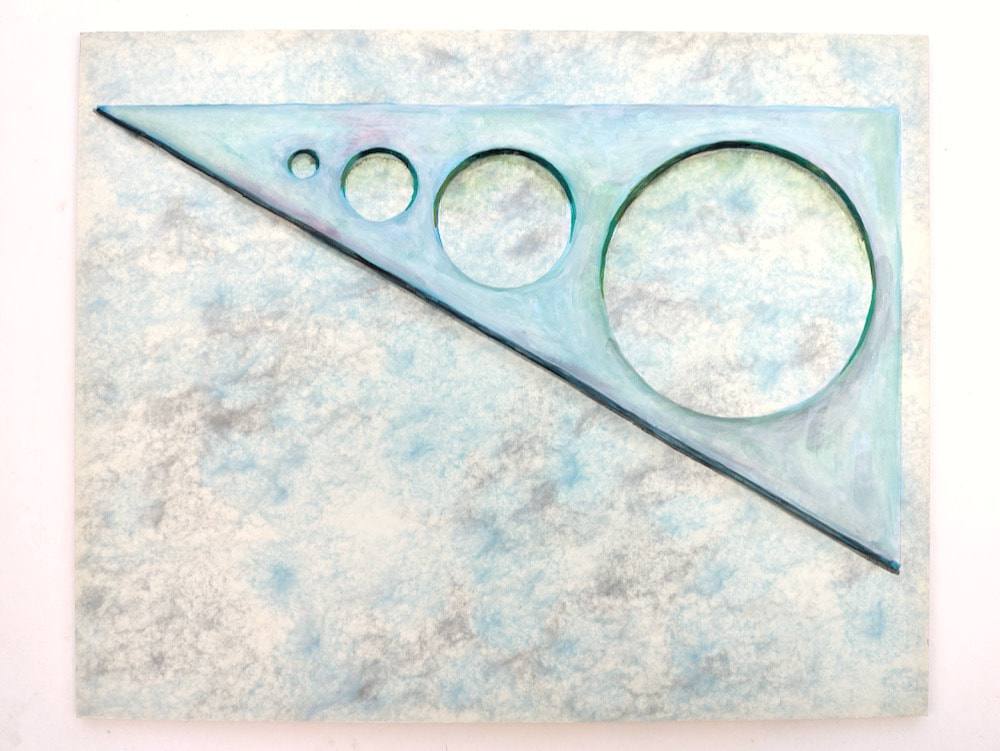

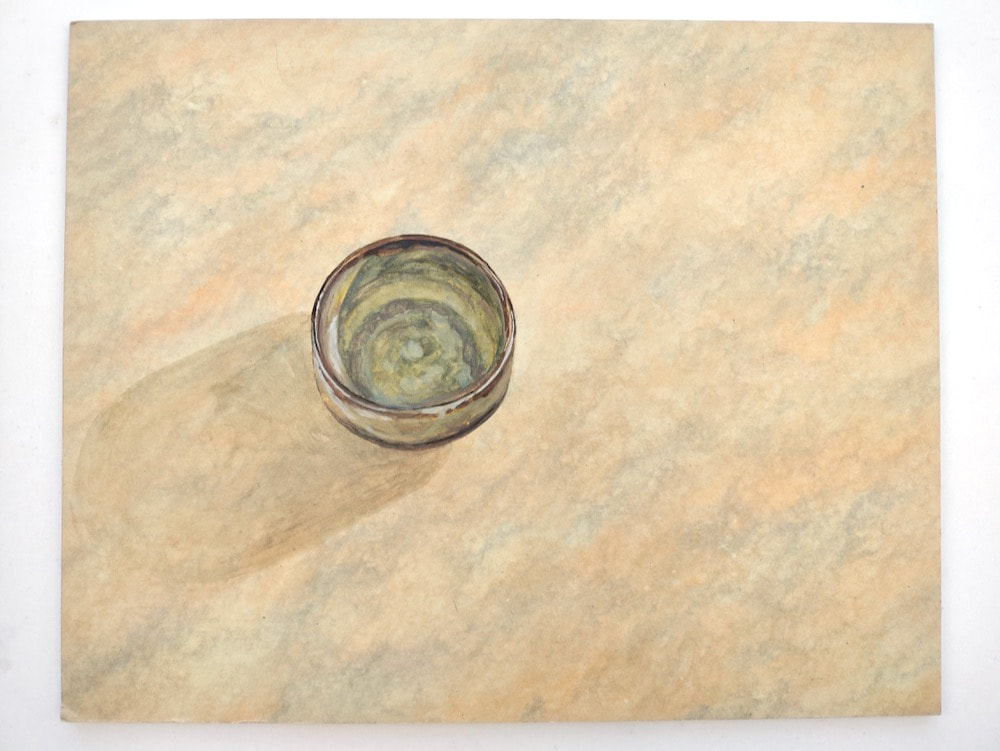

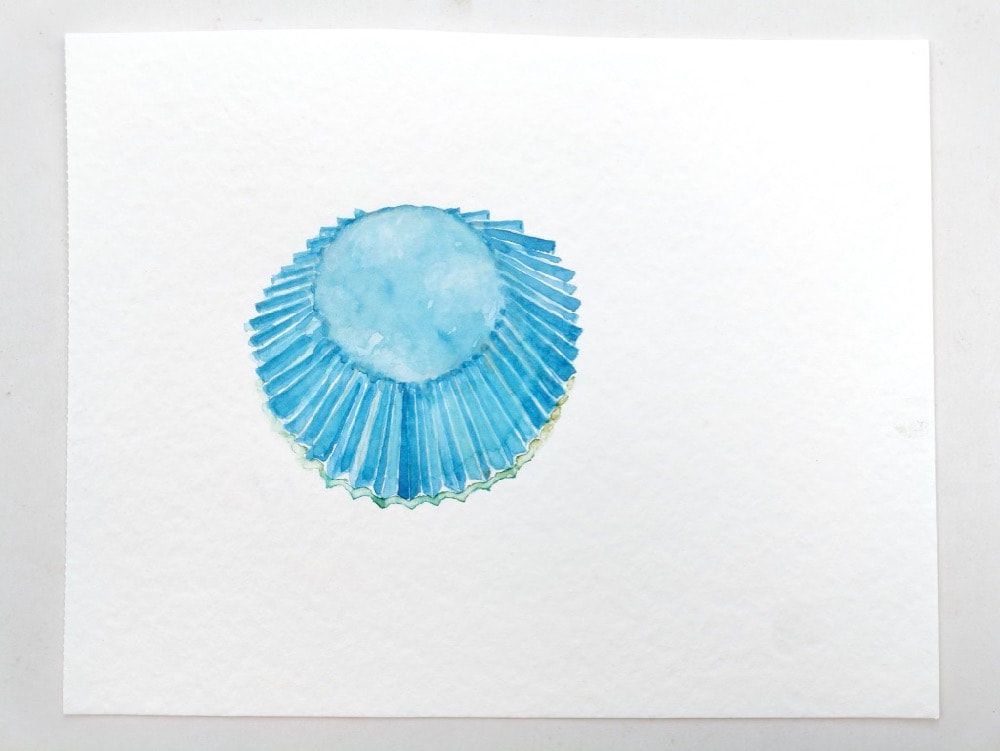

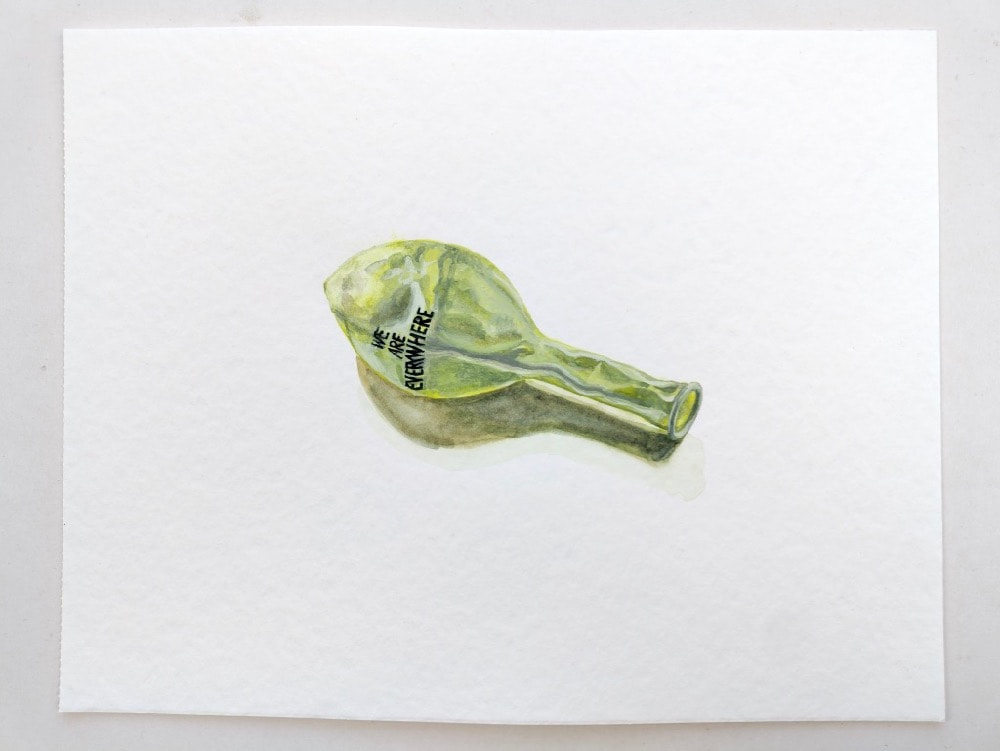

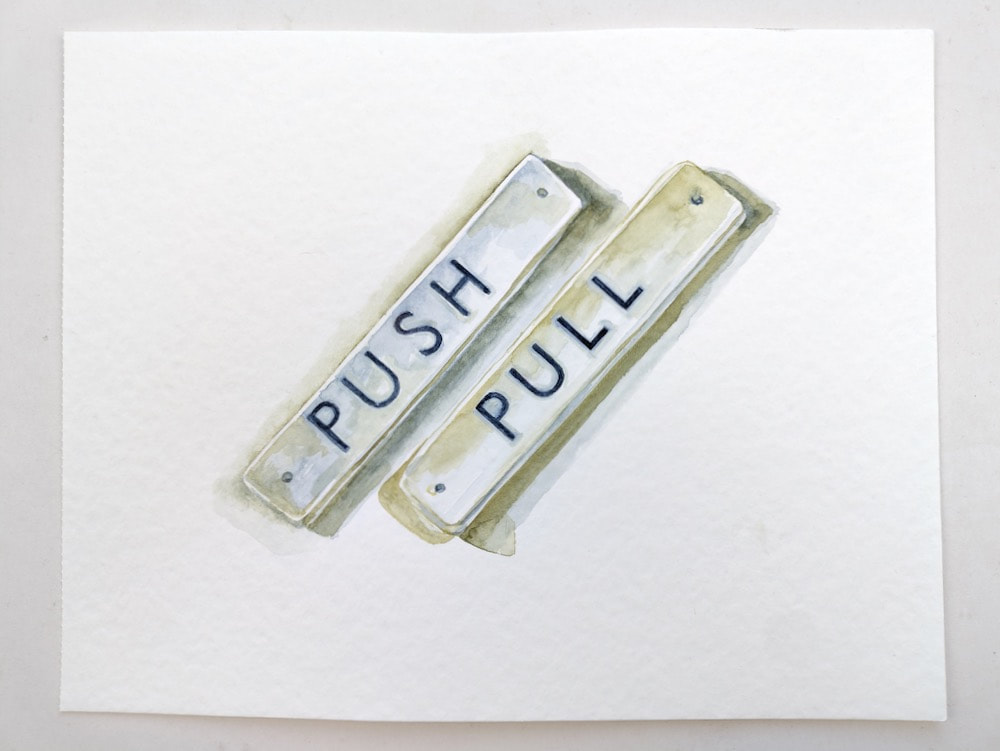

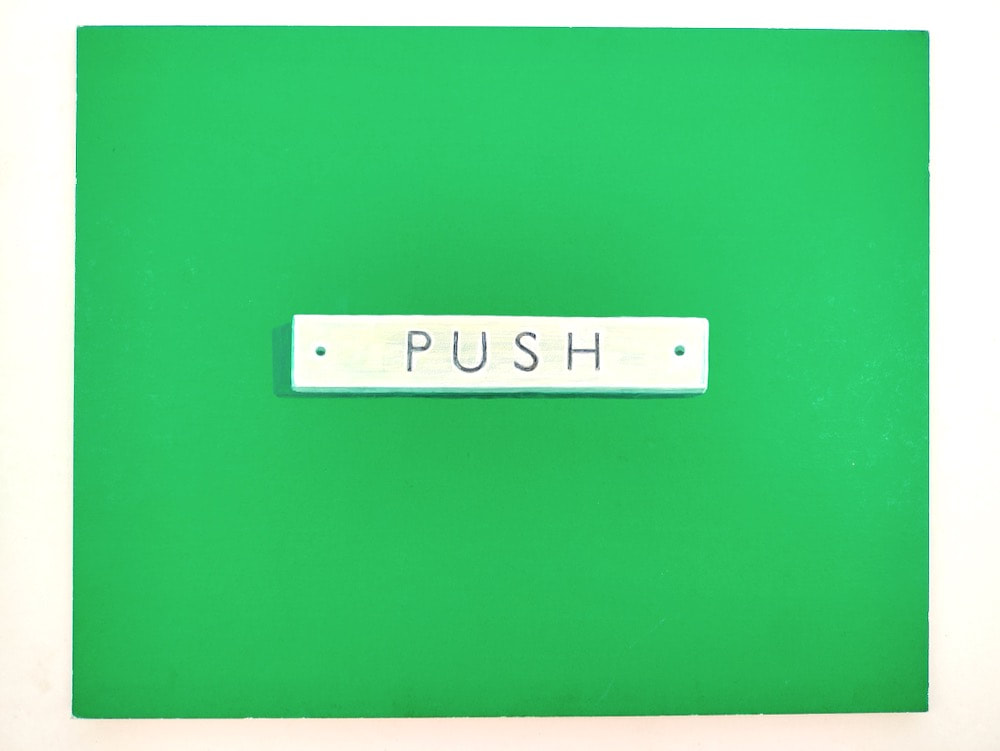

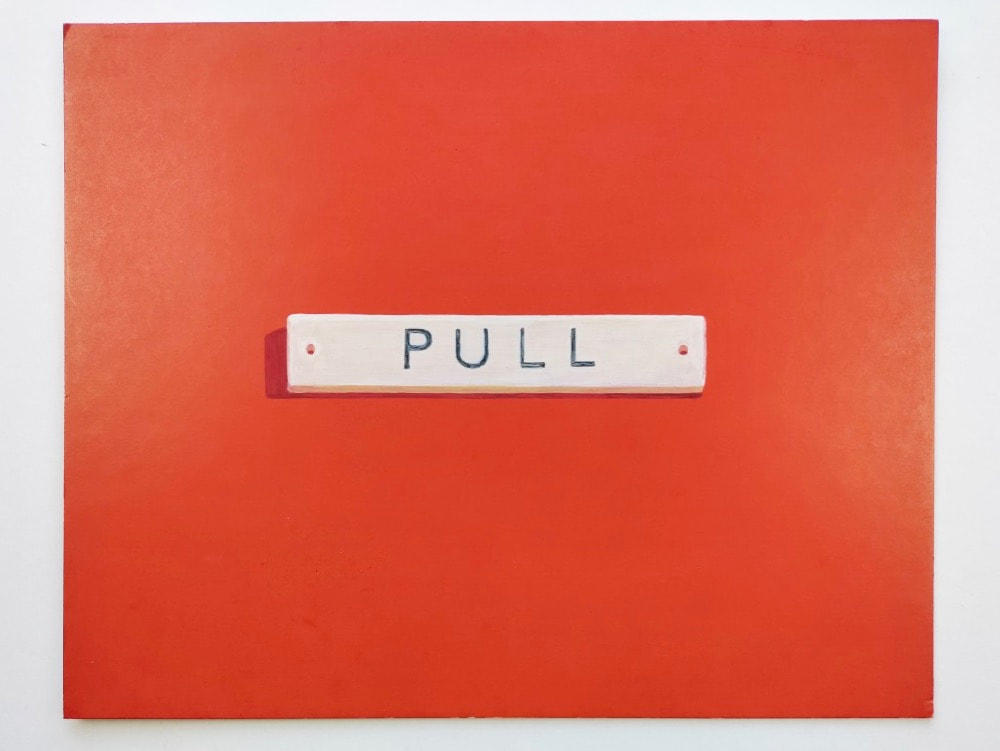

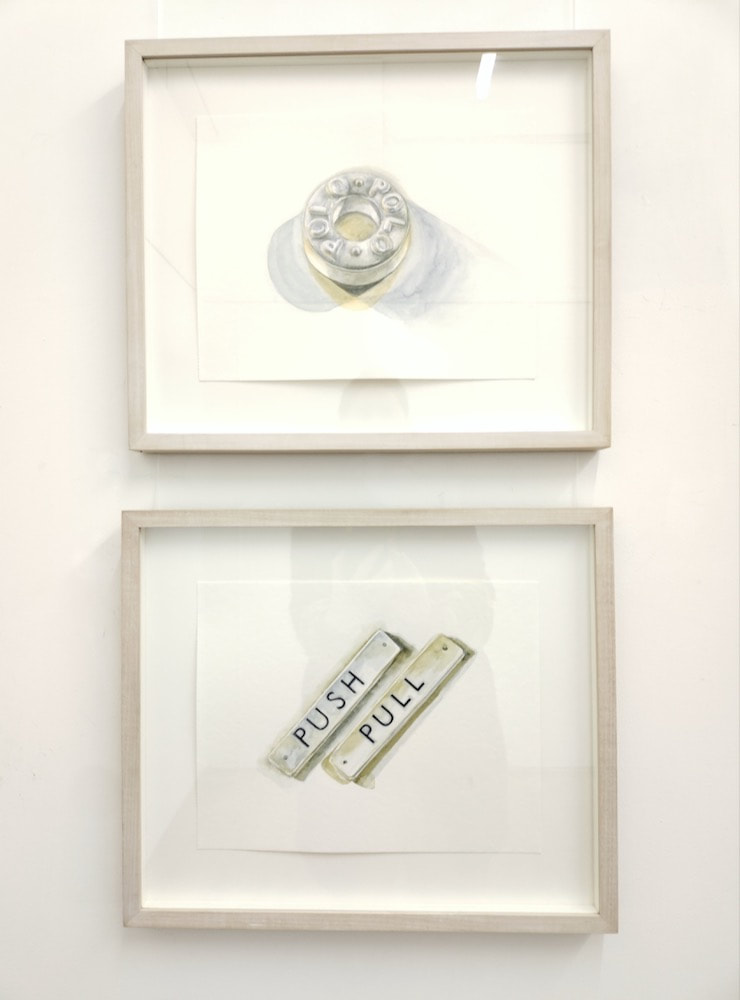

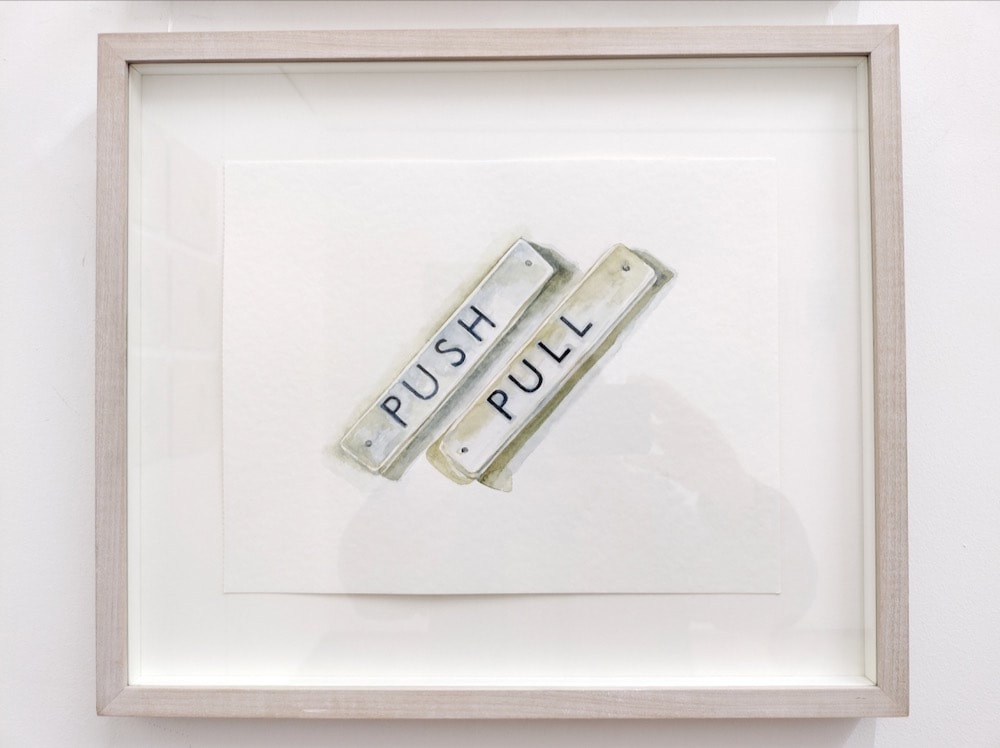

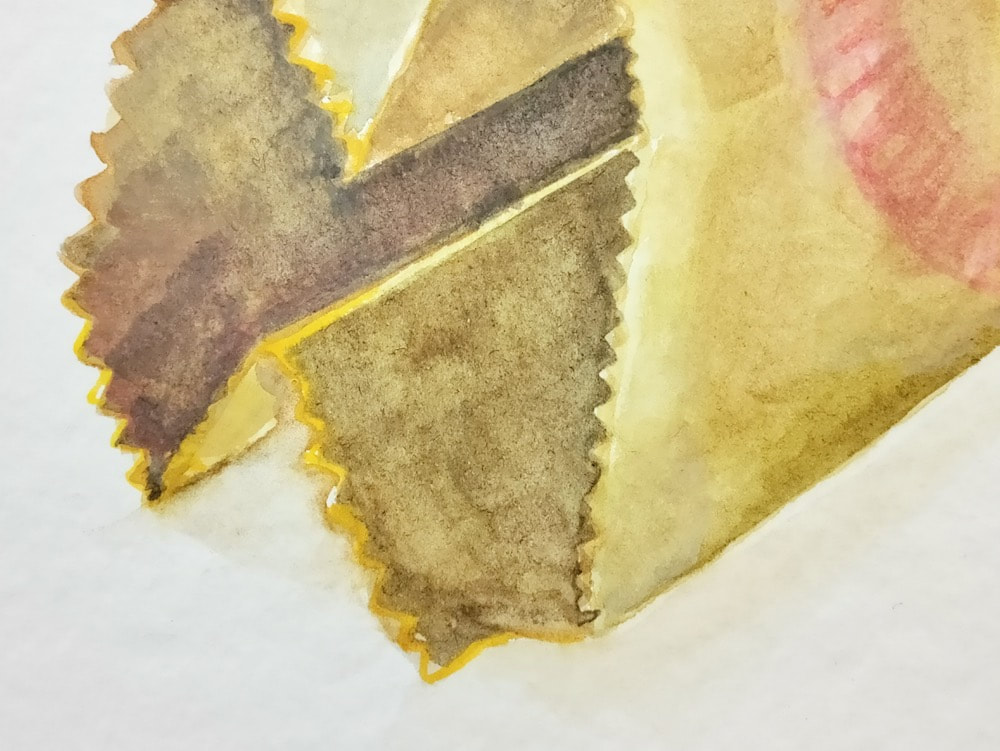

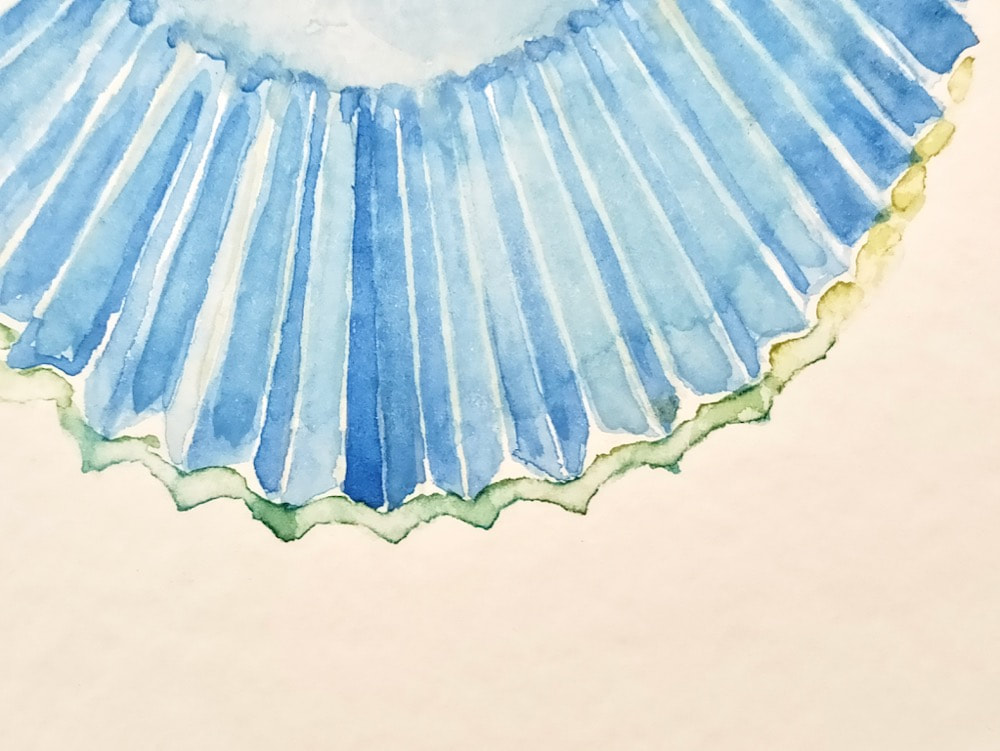

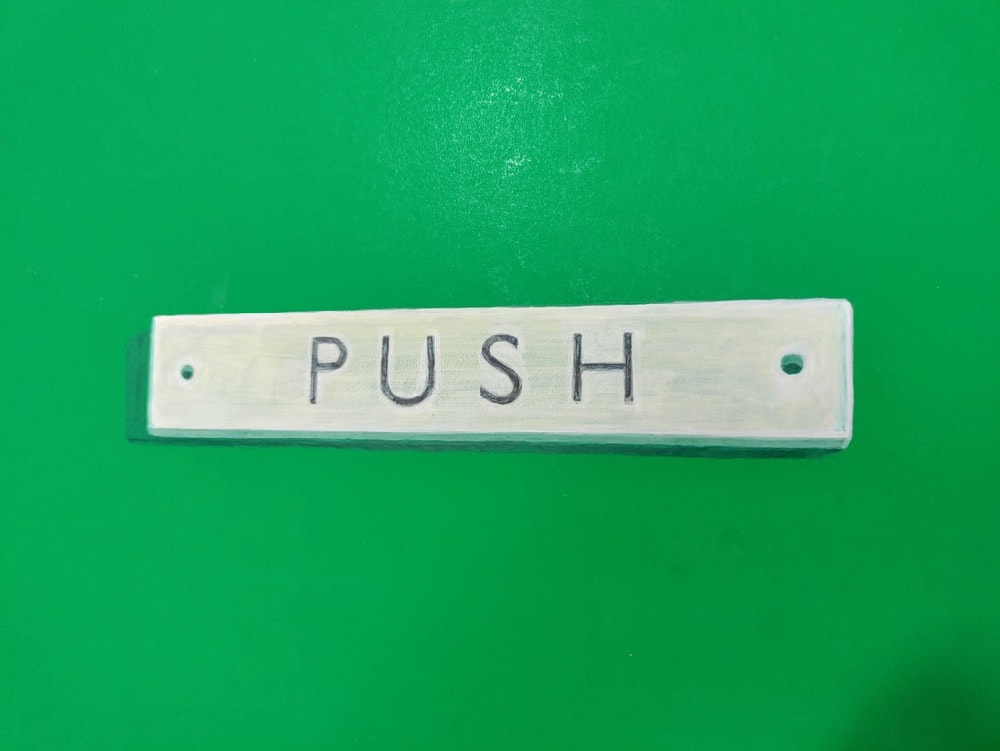

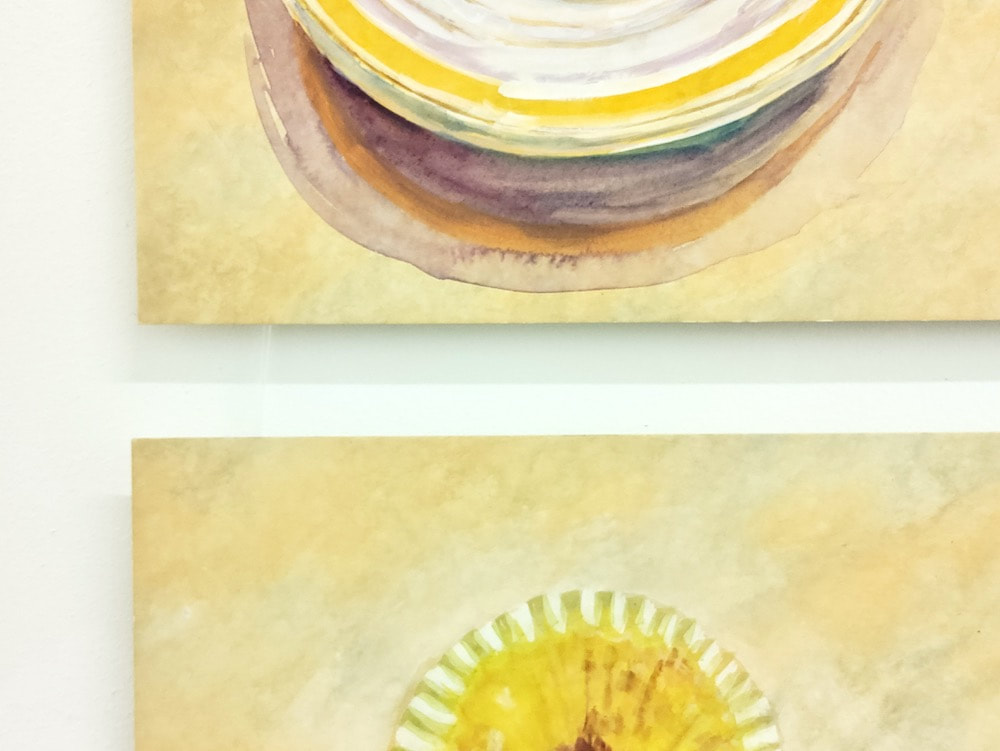

PUSH PULL (WATERCOLOUR STUDIES)

PUSH PULL HOLD STILL / CHIARA WILLIAMS

THE LIDO STORES / 24.03 – 03.04.2022

A solo show presenting a new series of 29 watercolour studies that shifts the tradition of still life painting into an episodic practice that is both prosaic and meditative.

THE LIDO STORES / 24.03 – 03.04.2022

A solo show presenting a new series of 29 watercolour studies that shifts the tradition of still life painting into an episodic practice that is both prosaic and meditative.

EXHIBITION TEXT

“A man will be imprisoned in a room with a door that’s unlocked and opens inwards, as long as it does not occur to him to pull rather than push” (Wittgenstein)

I’ve been thinking about ‘still life’. Not since school have I really thought too much about it. What a chore it seemed then. Compare the words ‘still life’ with the translation ‘natura morta’ and see the encapsulated meanings slip and slide etymologically, linguistically. I’ve also been thinking about why we even paint objects - conceptually, symbolically, literally and metaphorically - and why I’ve been painting them.

The still life tradition is inextricably linked to the notion of vanitas: paintings of a skull or fleshy fruit are established cultural stereotypes now, reminding us of our mortality. But until I started making these new studies, I hadn’t thought about how they might, in their own way, denote the emptiness, futility and worthlessness I was feeling, which is all inherent in the Latin roots of the word.

A forced confluence of chronic illness, parenting a young, challenging child, and on-off lockdown led me to some dark places. My most precious commodities - time and energy - were in short supply over the last 4 years. Until my body became sick, the exercise of painting what is ‘dead’ or ‘still’ or that which is ‘not life’ had never before brought me so decisively back to my own body. Painting these subjects became a refuge from my body, but it also anchored me in it and reminded me that I really can’t separate my physical and mental wellbeing from my work, as trite as that sounds.

I found sanctuary in the very few and relatively short pockets of a day when my time and energy converged in my studio. Most of the time I couldn’t make any work at all, but the studio also enabled me to stare at a wall, or into space, or read a book, or have a nap. Gradually, as I recovered, I started to be more productive in those spells and as my energy returned, I started to paint focused studies within a 20-25 minute time limit.

Painting objects that have outlived my grandfather (and which may well outlive me), on a stock of his own vintage artist board from the 1950s, has been strangely comforting and life-affirming. But, jostling together in my studio, even the lid of a jar, a recently used roll of tape, or a paper crown, are all equally held in a stasis; given a grace of permanence that will last at least as long as the painting does.

The scope and scale of my practice had to adapt and evolve, from an interest in ambitious installations and expansive context, to a simpler meditation on the small things around me every day. I have enjoyed the banality - in and of - these studies and they represent small havens of time that unexpectedly brought me stillness and joy, away from the push/pull of daily life.

At a time when many people have seen their worlds collapse in ever decreasing circles, when we’ve had to wait, hold on, stay still, I hope there is also a broader, universal appeal in these small works.

“A man will be imprisoned in a room with a door that’s unlocked and opens inwards, as long as it does not occur to him to pull rather than push” (Wittgenstein)

I’ve been thinking about ‘still life’. Not since school have I really thought too much about it. What a chore it seemed then. Compare the words ‘still life’ with the translation ‘natura morta’ and see the encapsulated meanings slip and slide etymologically, linguistically. I’ve also been thinking about why we even paint objects - conceptually, symbolically, literally and metaphorically - and why I’ve been painting them.

The still life tradition is inextricably linked to the notion of vanitas: paintings of a skull or fleshy fruit are established cultural stereotypes now, reminding us of our mortality. But until I started making these new studies, I hadn’t thought about how they might, in their own way, denote the emptiness, futility and worthlessness I was feeling, which is all inherent in the Latin roots of the word.

A forced confluence of chronic illness, parenting a young, challenging child, and on-off lockdown led me to some dark places. My most precious commodities - time and energy - were in short supply over the last 4 years. Until my body became sick, the exercise of painting what is ‘dead’ or ‘still’ or that which is ‘not life’ had never before brought me so decisively back to my own body. Painting these subjects became a refuge from my body, but it also anchored me in it and reminded me that I really can’t separate my physical and mental wellbeing from my work, as trite as that sounds.

I found sanctuary in the very few and relatively short pockets of a day when my time and energy converged in my studio. Most of the time I couldn’t make any work at all, but the studio also enabled me to stare at a wall, or into space, or read a book, or have a nap. Gradually, as I recovered, I started to be more productive in those spells and as my energy returned, I started to paint focused studies within a 20-25 minute time limit.

Painting objects that have outlived my grandfather (and which may well outlive me), on a stock of his own vintage artist board from the 1950s, has been strangely comforting and life-affirming. But, jostling together in my studio, even the lid of a jar, a recently used roll of tape, or a paper crown, are all equally held in a stasis; given a grace of permanence that will last at least as long as the painting does.

The scope and scale of my practice had to adapt and evolve, from an interest in ambitious installations and expansive context, to a simpler meditation on the small things around me every day. I have enjoyed the banality - in and of - these studies and they represent small havens of time that unexpectedly brought me stillness and joy, away from the push/pull of daily life.

At a time when many people have seen their worlds collapse in ever decreasing circles, when we’ve had to wait, hold on, stay still, I hope there is also a broader, universal appeal in these small works.